ANDRE LEU

The first mariners did not describe the vegetation on Four Mile Beach. As part of the research for this article I went through all the accounts I could find, beginning with Cook, Banks and Parkinson in 1770. I could not find any mention of the Four Mile foreshore.

The first detailed reports of the vegetation the region around Island Point were given by George Elphingstone Dalrymple in 1873. He named Island Point and was first documented European to sail upon the Mossman and Daintree Rivers. He described the hills and mountains as jungle-clad with some patches of well wooded open forests with grassy understories, however he did not describe the vegetation cover on Four Mile Beach or Island Point.

In April 1877 Christie Palmerston found the path from the Hodgkinson gold fields to Island Point by following an aboriginal trail down the Mowbray River and reported this to the Queensland Government.

An expedition was sent out in June 1877, to confirm if Palmerston’s path was suitable for wheeled vehicle traffic. It was led by William Oswald Hodgkinson, an experienced trail-blazing explorer, who had been part of the Burke and Wills, and other expeditions. His friend, James Venture Mulligan, who discovered the Palmer and Hodgkinson gold fields named the Hodgkinson River after him.

Hodgkinson gives us the first account of the original vegetation on Four Mile Beach, “there are about two miles of scrub to cut through on the top of the range, from which there is a good easy spur half a mile in length, which leads to the flat country near the beach. There are then four miles more scrub to cut through. The township will be on a sheltered cove adjoining the south side of Island Point…”

Scrub was the term commonly used at that time and well into the twentieth century to describe rainforest. Four Mile beach was originally littoral (littoral means coastal or waters edge) rainforest.

Island Point and the area around it, was covered in trees and patches of grassed woodland, “The site is splendid, a healthy spot, abundance of fresh water, well timbered and grassed, with a hard sandy beach…”

These areas are the result of the indigenous practice of cool burns to create a patchwork mosaic of mangroves, open woodlands with grass under stories and closed canopy rainforest around Island Point. Charlie McCracken described this in his historical account of Port Douglas, Mossman and Daintree regions with accounts of indigenous burning of the ranges behind Port Douglas.

Hodgkinson gives us clear evidence of the traditional owners’ occupation of present-day Port Douglas, “…a hard sandy beach, and soundings taken from a native canoe showed seventeen feet of water 200 yards from the shore.”

The descriptions given by early sailors describe these native canoes as long dugouts with double outriggers. They used paddles and some had sails made from woven palm leaves. The traditional owners had permanent settlements as well as temporary camps that they periodically moved to for hunting and fishing.

Very quickly in 1877 the town of Port Douglas (originally given several names) was surveyed and gazetted, and the Bump Road to the Hodgkinson gold fields was constructed. Merchants, government officials and others began to build the new town.

Clearing and cutting trees for timber, firewood for steam engines, cooking and other uses resulted in a new fire regime that completely changed the vegetation. Earliest photos from 1908 show that the original littoral rainforest has been replaced with sparse small bushes and trees growing in patches of bare sand.

Most of the rainforest species cannot tolerate fire and die when burnt. If there is enough soil moisture and the fire is a small cool winter burn, it generally extinguishes when it reaches the rainforest edge, without damaging the rainforest, because of the lack of readily flammable material.

Indigenous Australians practiced cool burns and created a mosaic of ecosystem types. Their burning did not destroy large areas of rainforest In the Wet Tropics. They co-existed with the rainforest for thousands of years.

However, this changed dramatically with the arrival of Europeans who actively cut down trees and used fire to kill rainforests to create cleared land for agriculture. The bulk of the rainforests in Australia were cleared by fire, not by the axe. Unfortunately fire is still being used to clear the last great rainforests of the Americas, Asia and Africa.

Rainforests are closed canopy forests. The dense canopy stops grass and other full sun species from growing under the trees, because they get shaded out. The cutting of trees for timber and firewood opens the canopy and allows grass to grow inside the forest. Dry grass is highly flammable and when burnt, the high temperatures kill the rainforest trees.

Port Douglas was no different. Fire killed the coastal rainforest. The constant burning prevented the rainforest from regenerating and instead species that tolerate fire such as Northern Wattle (Acacia crassicarpa), New Guinea Wattle (Acacia aulacocarpa), Beach Casuarina (Casuarina equisetifolia) and Stocking Gum (Corymbia tessellaris) began to dominate and form a new type of ecosystem.

Where there is good underground water, the Weeping Paperbark (Melaleuca leucadendra) survived because their thick papery bark protected them from fires. The largest of these trees are some of the only survivors from the original pre-1877 ecosystem. These Melaleuca trees can still be found in the Solander Boulevard, Reef St, Langley St and Barrier St areas. The signs of fire can be seen on some of them.

All of them should be fully protected and preserved as old historical trees. It is the worst sort of historical and environmental vandalism to cut down these old giants, and there should be severe penalties for destroying or damaging them.

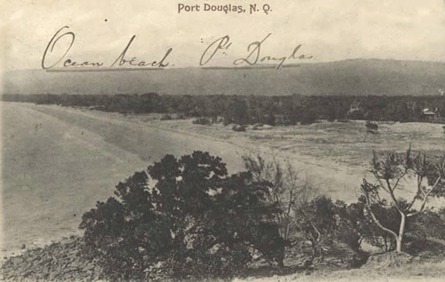

Four Mile Beach in 1908- mostly young low vegetation and large areas of sand with no vegetation

[Image courtesy of Douglas Shire Historical Society]

Four Mile Beach in 1908 from another angle.

Note the bare sand with minimal ground covers. This is due to regular burning destroying the original littoral rainforest types on Four Mile Beach. There is a clump of taller trees that can be seen halfway down the beach. These are the Melaleuca trees that can still be found in the Solander Boulevard, Reef St, Langley St and Barrier St areas.

[Image courtesy of Douglas Shire Historical Society]

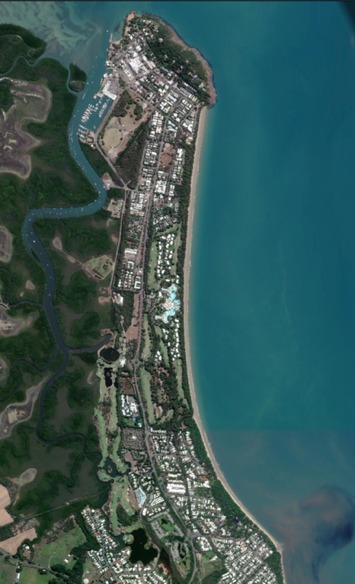

Island Point from the Light House in 1929. Island Point was almost totally cleared of trees.

[Image courtesy of Douglas Shire Historical Society]

By the 1930s the littoral forest on Four Mile Beach has been further degraded by regular fires. The rainforest species cannot regenerate as they cannot tolerate fire, Instead only fire tolerant species survive. Island Point is almost devoid of tree cover due to clearing and fires.

[Image courtesy of Douglas Shire Historical Society]

I first inspected Four Mile Beach in 1971 and it only contained a limited number of small fire resistant species. Most of the trees were small wattles, (Acacia Crassicarpa and Acacia aulacocarpa) with some Beach Casuarina (Casuarina equisetifolia) especially on the coastal fringe along with a few clumps of Cardwell Cabbage (Scaevola taccada).

Stocking gums (Corymbia tessellaris) grew further inland. Some Spinifex sericeus grow on the dunes along with Ipomoea pes-caprea, Canavalia rosea, and Cassytha filiformis.

Large remnant paperbarks (Melaleuca leucadendra) with some Sea Hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus) grew in the areas with ground water.

A survey conducted by Geoff Tracey and Len Webb in 1975 describes the area as Coastal Beach Ridges and Swales (the yellow section of the map below). The Wet Tropics gives the species composition as Ipomoea pes-caprea, Canavalia rosea, Spinifex sericeus and Cassytha filiformis. This gives way to a low, and often sparse shrub land comprising, amongst other species, Scaevola taccada, Premna serratifolia, Hibiscus tiliaceus, Acacia crassicarpa and Casuarina equisetifolia.

This ecosystem type is a result of fire. Wet Tropics management states that it needs regular burning for it to be maintained.

Port Douglas experienced decades of decline after Cairns became the major port due to the opening of the railway to Mareeba in 1896. The decline continued when the sugar wharf was replaced by the bulk sugar terminal in Cairns. The cheap land became popular for holiday homes for recreational fishing and also as permanent homes for the commercial fishing fleet. Consequently, Port Douglas began to slowly grow again in the 1970s and was largely a fishing village. The increase in residential houses along Four Mile Beach led to a reduction in the annual burning of vegetation and started the process of regeneration in limited areas.

The Sheraton Grand Mirage Resort was officially opened on Four Mile Beach in October 1987 by Christopher Skase. Almost overnight, Port Douglas changed from a quiet fishing village to a world renowned international tourism destination. A real estate boom resulted in the construction of residential homes and holiday accommodation.

Much of the existing vegetation was cleared for the Mirage and other developments as well as for housing. The regular burning of the vegetation ceased, and the remnant vegetation on the foreshore could regenerate back to littoral rainforest.

The vegetation map below was produced 30 years after Tracey and Webb by the Stantons in 2005. It shows most of the vegetation has been cleared, and that the vegetation types have changed. The most significant stand is the remnant Melaleuca leucadendra forest in the Solander Boulevard and Reef St foreshores (highlighted in light blue in the map below).

The small remnant areas of the coastal foreshore especially in the areas from Solander Boulevard to the Mowbray, started the process of regenerating back to the closed canopy littoral rainforest described by Hodgkinson in 1877.

Fifteen years later (2020) this process of succession from a secondary to a primary ecosystem is ongoing. Now that a canopy is forming and closing over the new forest, the next generation of new species is growing as part of the succession into a primary forest. This will still take another century, or more. Most of the trees in this forest are still quite young compared to similar old growth forests such as those along the Daintree Coast. The future generation of plants are now germinating and growing under the new canopy and will, over decades, change the species composition of this remnant forest.

It will still take a few centuries for this forest to fully regenerate to the old growth climax forest that was destroyed in 1877. Some of the larger long-lived trees such as Mastwoods and Banyans, after forty years of not being burnt, are starting to grow into good-sized trees, however it will take another hundred years or so before they reach the impressive sizes that can be found in old growth littoral rainforests.

I have deliberately chosen to stay away from the issue of exotic species and their roles in the regeneration process because it is complex and controversial. The critical issue now is to protect these remnant areas by minimising human disturbance and let them get on with the job of regenerating.

Nature will always regenerate ecosystems after they have been damaged, and she has been doing a great job in regenerating this ecosystem. We can help her by not disturbing and damaging her great work.

Think Different. Think DouglasNews.Network.

Your support matters. Support from our readers helps protect our editorial independence. Help us to report fearlessly on issues that affect our region, and to challenge those in power. Help us continue to deliver quality, trustworthy, fact-checked journalism that is free to access.

Unfortunately, unless you deal with the exotics – this recovery is unlikely to happen. I took the opportunity a while ago to look at the foreshore understory – a mess. How do you encourage people to do anything about it? “It’s not MY property”!