COUNCIL’S recent actions in permitting quad bike and ATV traffic on Wonga Beach, and the inevitable impacts it will have on our important (and World Heritage listed) ocean edge littoral forest, to say nothing of impact on shore-dwelling animals and birds, suggests that we neither understand its value or even value it.

HUGH SPENCER

For many readers, the term “littoral forest” may not have much relevance. In our neck of the woods, it would be considered “beach scrub”, not seen as pretty as ‘proper rainforest’ and “it’s in the way, cut it down, we want a nice seaside view from our deck”.

However, littoral, or ocean-side vegetation, is fast becoming one of the most endangered vegetation types in Australia, let alone the Wet Tropics (and the rest of the world).

So what is littoral forest?

It rather defies simple description, as it covers the range of vegetation that adorns our seashores and the forests that back them. Any plant growing near the ocean’s edge must have some amazing properties.

- The plant must be able to withstand a steady diet of salt spray (which for most plants, would be lethal)

- It must withstand continuous windy conditions (which when coupled with the salt spray, is a pretty big ask)

- It usually grows in an environment that is sandy and very nutrient poor

- It is patchy, ranging from luxuriant forests in spaces between headlands, to salt flats with mostly grass and halophilic (“salt loving”) plants such as Salicornia (Samphire)

Unfortunately, mangrove forests which live in the same environment, are officially excluded from the definition of littoral forests, yet they are just as critically important, suffer similar stresses, and provide an important range of “ecological services” – such as habitat for juvenile fish and filtering runoff.

Because there are so many different plant communities that are considered littoral, there is no “one size fits all” description. There is also a lot of uncertainty as to how far a littoral community extends into the coastal rainforest. Our Daintree Coast littoral vegetation ranges from very complex (with often large and well developed trees), such as at Cape Tribulation Beach (Kulki), to recovering littoral forests such as the Noah beaches and Myall beach. The Noah beaches (North and South) have had a long history of having been cleared for camping – and with those pressures now gone, they are recovering. Many of our beaches are graced with some iconic trees – the Beach Calophyllum would be one such, as is the Beach Barringtonia and the wonderfully smelly Morinda (cheese fruit).

Beach littoral forests can provide protection against beach erosion by acting as “shock absorbers” to incoming wave action. This can be observed on beaches such as Cape Tribulation beach (Kulki) which has one of the best local examples of a complex tropical littoral forest.

Littoral forest on the northern Wet Tropics World Heritage section of Wonga Beach protects an endangered dune-swale system (a series of parallel small sand dunes with remnants of small lagoons (swales) between them).

Fauna / Unlike many areas in the world, our littoral forests are rather lacking in large fauna. We have the white tailed rat, we have bats and flying foxes, but we don’t appear to have significant breeding colonies of birds as many islands do. This is just a reality that would be interesting to investigate further.

Sea level rise and storms / We would hope that littoral forests can protect our shorelines against rising sea levels. Well they can, provided they can stay intact and are able to retreat as the sea levels rise and the storm incidence rises. It’s a big ask. Littoral forests which are in the “reach” of South East winds and heavy seas, such as Cape Kimberley and several other beaches, will always lose ground. Sometimes this ground will be recovered, but with projected increasing storm disturbance and rising sea levels, the best we can do is to maintain some degree of beach littoral forest integrity.

Threats to Littoral Vegetation

The opening of Wonga Beach to vehicular traffic highlights the reality of the threats that our activities pose to littoral (seaside) vegetation and to animals that live there. There are now also reports of numerous incursions by people into the bordering coastal forest and their lighting fires.

This leads us to the vexacious issue of weeds. The strangely named “transformer weeds” (no, they don’t change shape) are weeds that can transform the environment. For the littoral forests, at least in this region, the major weeds are pond apple, Singapore daisy and, shock-horror, coconuts.

Pond apple (Anona glabra) is closely related to soursop (and was brought into north Queensland as rooting stock for custard apple and soursop) and has grown feral. Incidentally, it is also considered one of the Florida Everglades rarest native trees. Pond apple is highly invasive, produces lots of long lasting floating seeds, and is loved by flying foxes and a variety of birds. It has become a major invasive of swampy areas (and is costing the Queensland State Government millions in control efforts). Luckily it doesn’t usually invade beach areas – the seeds germinate but usually die.

Next on the list is Singapore daisy (Spagneticola trilobata). This beautiful little yellow flower from Brazil (introduced as a lawn substitute) is now the environmental scourge of much of eastern Queensland. It is highly invasive of disturbed ground and can create an almost complete monoculture. Many of our northern beaches have been overrun with Singapore daisy, which also completely suppresses native littoral regeneration.

Not for nothing it is considered a “transformer” weed. However, it has two aspects going for it. Firstly, it produces very little seed (but it does produce some). Secondly, there is a very effective and amazingly selective (and cheap and relatively non toxic) herbicide which can completely eliminate it. Learn more here.

At Austrop, we have managed to clear approximately four kilometres of Daintree Coast beaches of Singapore daisy using this herbicide (and the littoral recovery is fantastic). But, because Singapore daisy does produce some seed, the beaches will need yearly revisits. However, we also need to consider upstream sources of infestation and if possible eliminate them, as floods carry the seeds and plant fragments onto the beaches.

Next to consider is the major transformer weed.

Coconuts (Cocos nucifera).

This seems to be the plant about which rational discussion and action becomes unstuck. The image of coconuts has been appropriated by the tourism and travel industry as ‘shorthand for “The Tropical Experience” and this image seems to have become thoroughly embedded in the local psyche.

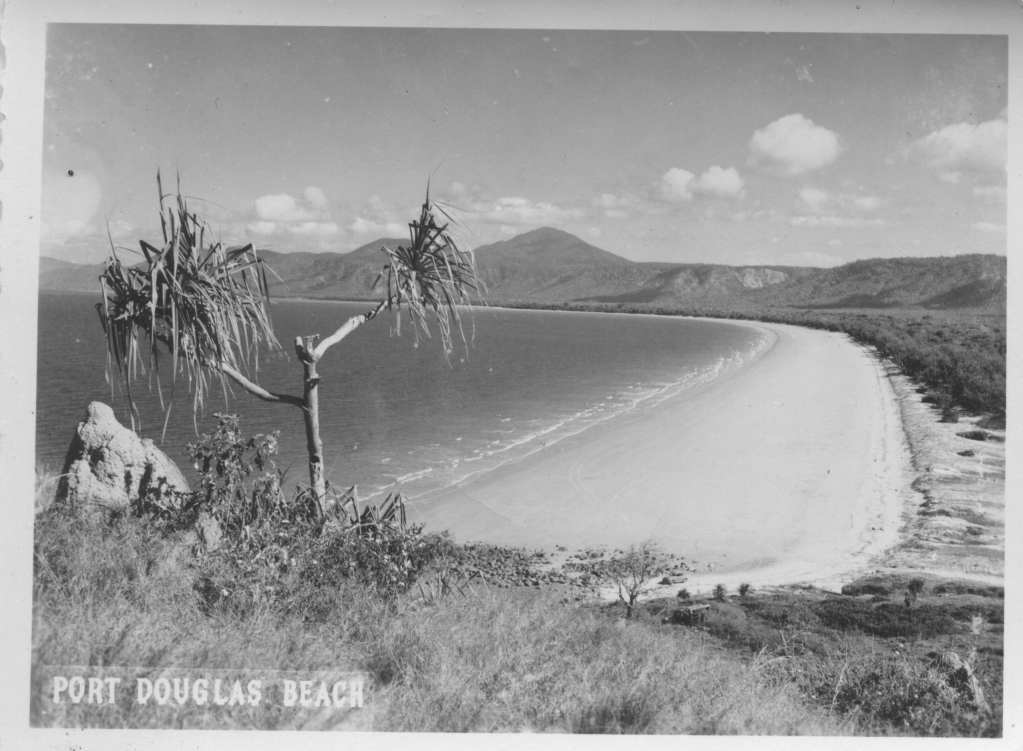

Maybe we should be promoting this:

As a result, efforts to address the coconut issue by past Councils and others has met with determined and ferocious local hostility.

A bit of historical information – coconuts are not native to Australia and there was a sustained effort to plant them by the Colonial Office in the 1800’s to provide succour for shipwrecked sailors.

In the 1930s and 1940s coconut plantations were set up along the coast, most of which are now gone. In the 1960s with the ‘hippie’ influx to the area, coconuts (seen as the “tree of life” – free dinner!) were planted all along the coast. In the mid 1950s there were no (or very few) coconuts on Four Mile Beach!

Unfortunately not all coconuts are identical (there are many varieties, depending on whether they were bred for fibre or meat. (copra)). So we have low fecundity coconuts (only a very few nuts actually ever germinate before the white-tailed rats get to them) and we have high fecundity coconuts which produce lots of nuts, which all sprout, and produce a thicket of coconuts, This seems to be the situation on Four Mile Beach. It is also the situation in places such as North Cowie Beach, where an otherwise isolated World Heritage area (which used to resemble Cape Tribulation Beach) is now fast being over-run with high fecundity coconuts and we are seeing the same at northern Wonga Beach.

This problem is not unique to this area – the coral atolls of the remote tropical Palmyra Atoll are over-run with coconuts – which have destroyed much of the littoral forest (which is critical for bird breeding in this remote Pacific region). These coconuts were brought in by early sailors and have caused major damage – which is now being addressed by the US Forest Service through serious removal.

Unfortunately coconuts don’t protect littoral forests against ocean forces. Native littoral plants such as Scaevola (beach cabbage) and Sophora (necklace bush) and others are very effective shock absorbers, but water just flows around coconut bases.

Coconuts also present another major problem for littoral forests, they drop large and heavy fronds that squash native seedlings (as well as shading them out). They also produce masses of nuts – which cover the ground – walking in high density coconut areas is like walking on skulls, plus the broken (or rat-chewed) nuts are great mosquito breeding sites. In fact walking on fallen coconuts can be a very risky exercise for visitors.

Control / Well, do exactly what they are doing on Palmyra Atoll. Sure, you can chainsaw the adults, but that creates massive damage on the ground (they are very heavy). Chop the juvenile sprouts off close to the nut, “drill and fill” the adults (the preferred method), this leaves the trunks standing and they will rot from the top and natural regeneration can occur around the dying trunks. But it doesn’t look good for a couple of years – maybe some education is required!

If it is perceived that coconuts are essential for the image, then identify and remove the high fecundity trees, which is easy to do as they have so many sprouting juveniles around them. Leave the low fecundity ones as white tailed rats and tourists will control them.

Other Threats to our Littoral Vegetation

We have discussed invasive weeds in the last section, however they are not the only threats.

Clearing / There are many examples of illegal clearing of littoral communities by landholders (“to provide a clear view through the lovely coconut palm trunks”), especially on Four Mile and Wonga beaches, this is a further serious pressure on our very limited littoral areas. The opening of Wonga Beach to quad bikes is a further concern for those littoral areas.

Some of the areas of illegal clearing are quite extensive – and there appears to be little appetite by the Council for regulating this (as most of the clearing is done on Esplanade zoned land which is public and is Council’s responsibility).

Image Credit / Jayne Miller

Protection / In theory anyway, our littoral plant communities here are protected by being under World Heritage, the reality is that they appear to fall into an administrative blind spot, and very little, if any, effort is put into their protection.

So who is responsible for their protection?

Supposedly,

- Council, where the land is zoned as Esplanade

- Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, where otherwise zoned

- Wet Tropics Management Agency, where land lies within World Heritage status.

In reality, sadly, with the general funding cuts for environmental activities, these organisations have insufficient resources to perform their environmental responsibilities. As a colleague in one of these organisations reports, “the upper echelons are exceedingly reluctant to cause any public backlash”. “Maintaining my mortgage is more important than the environment” as another colleague confided to me, reflecting a general sense of staff insecurity.

In fact Douglas Shire Council appears to have become very hostile to those independently attempting to control invasive weeds on public land (which includes littoral vegetation and roadsides). Much of this seems to stem from increasingly complex conditions imposed by State and Federal Governments, largely driven by OH&S/WPH&S, which local Councils are obliged to follow. Plus there are Council concerns with possible litigation should any non-Council person sustain an injury and attempt to sue the Council. As a result, with reduced funding and reduced support for environmental action both at Council and Governmental level, the weeds are having a field day.

This situation seems quite resolvable, but there appears little interest in doing so.

One suggestion is a two-day training workshop (free, supported by Council). This would provide information on appropriate control techniques. weed identification, herbicide use, (real) safety issues, and at the end, participants should be given a suitable ID card and should be covered by something like Austcover insurance (funded by Council) while they are involved in conservation activities. We also urgently need community education about the realities that we face.

A complicating issue is what appears to be an increasing level of “chemophobia” in the community which can result in verbal and even physical attacks on people (including Council staff) performing weed control, or any environmental work, in the public eye. This is a very difficult issue to address, and can be very discouraging to workers. Councils are also required to respond to complaints (even if malicious or vexacious) which can be very time consuming for Council staff, (although the proposed ID card would assist here).

If you are interested in touring the range of intact littoral forests north of the Daintree – may I suggest the following locations:

- the northern end of Cow Bay Beach (only at low tide) – there are some magical and different types between the outcrops.

- South Noah Beach (a long walk to the mouth of Noah Creek and back)

- North Noah Beach

- Myall Beach (although the northern end has a bad coconut infestation)

- Cape Tribulation Beach

- Emmagen Beach (trail starts near the big fig tree).

Aren’t they wonderful?!

About the Author / Dr. Hugh Spencer is a conservation biologist who lives at Cape Tribulation. He established the Cape Tribulation Tropical Research Station over 30 years ago, which is operated by the Australian Tropical Research Foundation (Austrop). The property is also a nature refuge (Cluster Fig).He and many students, interns and volunteers have been instrumental

in rainforest and littoral forest regeneration and weed control on the Daintree Coast.